Last Night a Critic Changed My Life

Jackie Hedeman on Roger Ebert’s secular humanism

Welcome to the Partisan series "Last Night a Critic Changed My Life." Echoing a long-running feature in Mojo Magazine, which looks at life-changing records, this series will focus on moments when writers encountered the work of a critic and found themselves transformed.

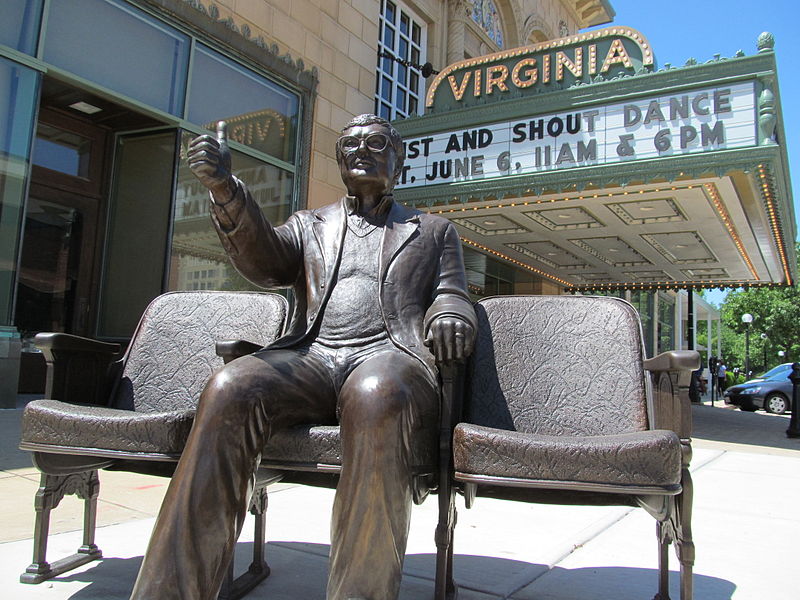

Photo Credit: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

FOR A FEW years there, I filled out the Proust Questionnaire more or less annually. When I stopped, it was because my answers were becoming predictable. I was solidifying. “Who are your heroes in real life?” Roger Ebert, I answered again and again.

I never met the man, but every Saturday morning, I scanned the bulletin board at the Urbana, Illinois Free Library, where the librarians posted Ebert’s reviews for the movies playing in town (our town, the hometown we shared). We had two multiplexes, which grew increasingly multi over my childhood and adolescence, and one art house downtown, conveniently called the Art Theater. At the Art, I watched Spirited Away, Capote, Brokeback Mountain, The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo (Swedish version, naturally), Broken Flowers, Howl’s Moving Castle, Caché, The White Ribbon, Amélie, Lost in Translation. At the multiplexes I watched Harry Potter, Lord of the Rings, The Secret Garden, Little Women, Jane Eyre, other movies that weren’t adapted from books: a whole eighteen-year catalogue of taste formation.

The first movie I went to see in theatres was Disney’s Beauty and the Beast. I was three years old and I carried our smuggled-in candy in a chicken-shaped purse. I liked the movie, and thought the wolves were scary. Ebert wrote:

The film is as good as any Disney animated feature ever made… And it's a reminder that animation is the ideal medium for fantasy, because all of its fears and dreams can be made literal. No Gothic castle in the history of horror films, for example, has ever approached the awesome, frightening towers of the castle where the Beast lives. And no real wolves could have fangs as sharp or eyes as glowing as the wolves that prowl in the castle woods.

The pattern was set, though I didn’t know it yet, wouldn’t for years. With only a handful of exceptions, if I liked a movie, Ebert did too.

I have tried to figure out why this is. Taste is the height of subjectivity, a product of nature and nurture and, what? Circumstance? Habit? The things we pick up and put down along the way? What combination of factors could yield the kind of man who would write of E.T., “This movie made my heart glad”? I may as well ask why we do anything at all.

As a critic, Roger Ebert practiced the empathy of not knowing. Even after filing thousands of reviews, he remained curious, impressed by movies and what they could accomplish. Ebert worked on an international stage, first reviewing movies for the Chicago Sun-Times and then as a syndicated columnist. On TV alongside the Chicago Tribune’s Gene Siskel, Ebert made his name doling out thumbs up and thumbs down. He approached movies as a movie lover. In his review of Star Wars: Episode IV A New Hope, Ebert wrote, “My list of other out-of-the-body films is a short and odd one, ranging from the artistry of Bonnie and Clyde or Cries and Whispers to the slick commercialism of Jaws and the brutal strength of Taxi Driver. On whatever level (sometimes I'm not at all sure) they engage me so immediately and powerfully that I lose my detachment, my analytical reserve. The movie's happening, and it's happening to me.”

If I can claim that Ebert’s four star-reviewed films share anything, it may be that within them, Ebert found a story universal enough to access, and particular enough to trust. Of Spirited Away, Ebert wrote, “Miyazaki says he made the film specifically for 10-year-old girls. That is why it plays so powerfully for adult viewers. Movies made for "everybody" are actually made for nobody in particular. Movies about specific characters in a detailed world are spellbinding because they make no attempt to cater to us; they are defiantly, triumphantly, themselves.”

“As a critic, Roger Ebert practiced the empathy of not knowing.”

As far as I can tell, to even approximate the experience of watching a film the way Roger Ebert did, you must first zoom out. Ebert himself said that his film criticism was “relative, not absolute.” He compared films to others within the same genre or the same framework of values. So a plot-heavy drama would be compared to other plot-heavy dramas, and an explosion-fuelled action film would be compared to other explosion-fuelled action films, and both of these would be reviewed through the lens of the world Ebert lived in. The result of all of this relativity was secular humanism to marvel at.

What of Ebert-the-human? What of his particulars, and how they inform his universal appeal, or at least his appeal to me? Let’s begin with our shared hometown: aquifer-grounded twin cities Champaign-Urbana, Illinois. The place is, I insist at my most defensive, a great place to grow up. It has that split identity unique to Midwestern college towns: a humming curiosity, a quiet grunge. It’s the kind of place that belches out STEM Nobel laureates and famous bearded creatives at a more or less equal rate. Many of them leave and never come back.

Ebert left for Chicago, but he also came back. And he brought Hollywood with him. Roger Ebert’s Film Festival, which Ebert founded in 1999 and attended until his death, “celebrates films that haven’t received the recognition they deserved during their original runs.” Ebertfest runs for four days each spring not in Chicago, where Ebert made his name, but in Champaign’s creaking, beloved, 1920s-era Virginia Theatre. Ebertfest brings people like Tilda Swinton to Champaign. The festival has brought Donald O’Connor and Shailene Woodley and everyone in between. I wonder where they stay when they’re in town.

There are two kinds of hometowns: the kind you love and the kind you never want to see again. Both outlooks skirt the sneaking, sinking suspicion that it’s just another place, one of many. I loved Champaign-Urbana, and when I go back I sometimes cringe to find it somehow different. Less something. More something else. Nearly ten years gone from the place, I look at Roger Ebert’s decision to bring Ebertfest back home and my glee is tinged with admiration. In his place, would I have made the same choice? Whether he experienced Champaign-Urbana as wholly unique or deeply ordinary, he recognized that he was lucky to know it so intrinsically. Sometimes I think I share his certainty. Other times, I’m reminded of the gulf between us. All our surface similarities—only child, raised Catholic, English major—spread unevenly across the face of our Midwestern-ness; they may begin to explain why I take Ebert’s writing so personally, but they don’t even begin to gesture at a whole person, let alone two.

IN HIS REVIEW of 28 Up, Ebert writes, “Somewhere at home are photographs taken when I was a child. A solemn, round-faced little boy gazes out at the camera, and as I look at him I know in my mind that he is me and I am him, but the idea has no reality. I cannot understand the connection, and as I think more deeply about the mystery of the passage of time, I feel a sense of awe.” I note how many of the attributes I share with Roger Ebert are grounded in childhood, bound to be lost or diluted with every step away from home. I wonder how much of my admiration is influenced by a desire to recapture something I was always supposed to lose.

“There are two kinds of hometowns: the kind you love and the kind you never want to see again. Both outlooks skirt the sneaking, sinking suspicion that it’s just another place, one of many.”

I want to be a careful reader, and I suspect that’s who Roger Ebert was—of film and text and people. Ebert notably included The Birth of a Nation in his list of Great Films, and devoted the majority of his review to explaining the necessity of his choice.

To understand The Birth of a Nation we must first understand the difference between what we bring to the film, and what the film brings to us. All serious moviegoers must sooner or later arrive at a point where they see a film for what it is, and not simply for what they feel about it. The Birth of a Nation is not a bad film because it argues for evil. Like Riefenstahl’s The Triumph of the Will, it is a great film that argues for evil. To understand how it does so is to learn a great deal about film, and even something about evil.

Real life doesn’t end when the lights go down, or resume unchanged when they go up again. A hallmark of Ebert’s reviews is that his commentary reached beyond the screen, past the seat he chose, into the hallway and out of the movie theatre to implicate us all. Everything is an image on a cave wall. The best we can do is watch.

JACKIE HEDEMAN is an MFA candidate at The Ohio State University, where she serves as Reviews & Interviews Editor for The Journal. Her work has appeared in Watershed Review and is forthcoming from The Manifest-Station.

LINDA BESNER talks to NYLA MATUK about her new book