Paul Bernardo's Thriller and the Banality of Evil

Sarah Marshall on a book that isn't good enough to be bad

Gary Oldman and Kevin Bacon in Criminal Law

YOU PROBABLY HAVEN'T seen Paul Bernardo’s favourite movie, because no one seems to like it except Paul Bernardo. If you think that’s because it was too brutal, too graphic, and too in keeping with his sadistic desires to be suitable for the public, then you are, unfortunately, wrong. Simply put, you probably haven’t seen it because it isn’t any good. Criminal Law—a 1988 thriller that was, like Bernardo himself, a Canadian production doing its best to look American—stars Kevin Bacon as serial killer Martin Thiel and Gary Oldman as Ben Chase, the defense attorney who slowly gets sucked into Martin’s world. The plot is contrived, the suspense is minimal, and the highlight of the movie is Kevin Bacon’s performance as a remorseless killer. Everyone has forgotten it—everyone except Paul Bernardo. Why?

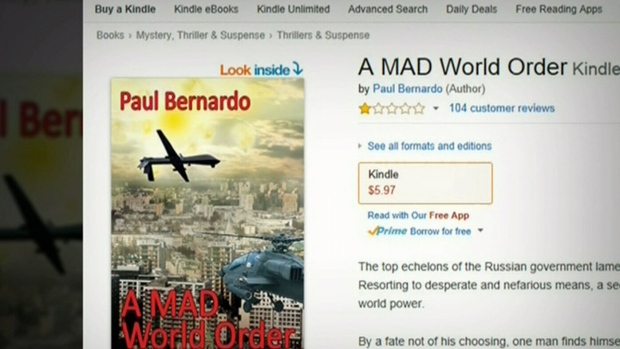

Bernardo’s artistic taste made headlines late last year when his own attempt at a thriller, an Amazon-distributed eBook called A MAD World Order, was first discovered on and then suddenly yanked from the site. The book is now gone without a trace, but 636 one-star reviews are still visible. In them, the rage that spurred Amazon to erase the book is clear:

I am completely amazed that this [piece of shit] has been allowed to publish and sell a book. He is a convicted murderer and should definitely not have that right.

have cancelled my amazon account and credit card and will never deal with a company that knowingly deals with paul bernardo.

Don't buy this book! I would never buy it and support a mass murderer.

I am seriously disappointed in Amazon, to allow such a disgusting product to be sold on their websites. I feel greatly for the families of Bernardo's victims that they would have to go through the pain of their loss again through the publication of this despicable book.

I will never purchase nor read anything that will profit Paul Bernardo, a heinous, unrepentant torcherer and murderer of girls and women!

Amazon....you have lost me as a customer forever. Carrying the work of a sexual sadist, murderer, monster??? I will NEVER purchase from Amazon again

TO PUT ONE THIN DIME IN THIS MONSTERS POCKET IS BEYOND COMPREHENSION! … Please Amazon have some compassion for the families that this ANIMAL has destroyed. Who cares what stories he has to tell, or any others like him.

Almost none of the Amazon reviews of A MAD World Order actually review A MAD World Order, and neither will I: I can’t. The book disappeared from Amazon last month after it prompted outcry not just from Amazon reviewers but from Tim Danson, who represents the families of Kristen French and Leslie Mahaffy, the teenagers Paul Bernardo was convicted of murdering in a highly publicized trial in 1995. For the French and Mahaffy families, Danson told the CBC, news of the book merely reopened old wounds. “They don’t want to be thinking about him,” Danson said. “They don’t want to be talking about him.”

But there was, Danson argued, some hope of a silver living. The book, a violent spy thriller, might be enough to eradicate even the vague possibility of Bernardo securing the day parole he infamously applied for in 2015. Its gory scenes, Danson said, offered yet more support of the public’s opinion of Paul Bernardo: “once a psychopath, always a psychopath.”

“I haven’t come across a single post in which anyone, even the most avid of Bernardo’s fans, will admit to having read it.”

It’s still unclear to me whether A MAD World Order disappeared not just from Amazon but from the reading devices of the people who already bought the book. I’m having such trouble uncovering this information because, no matter how many people I ask, no one will admit to actually having bought it. I’ve prowled subreddits dedicated to murder and mayhem, emailed journalists who covered the outrage surrounding the publication, and even messaged Tumblr users who are unafraid of telling the world that they would read a book by an “unrepentant torcherer,” that they care “what stories he has to tell.” Even they aren’t talking.

These are the fans of Paul Bernardo, and for the most part they aren’t shy about talking. They are also, it seems, mostly young women. When they aren’t posting about Bernardo, they post about depression, self-harm, and Lana Del Rey, whose lyrics echo just a little too eerily the kind of mental state that his wife, Karla Homolka, claimed to have had during the years she aided in his crimes: a love that was addictive because it was so toxic; a love in which a man exerted astounding power over a woman by making her feel he needed her in order to survive, and that she is special because she might just be the one to save him.

Bernardo's fans post about a lot of things, but they always come back to him. They post pictures and gifs of him in his younger years (him rapping, him dancing on the lanai during his Hawaiian honeymoon, Paul and Karla at Christmas, Paul and Karla, Paul and his girls). They post about wanting to write to him, (“Its deep in my bones and i cant let it go”) about writing to him and screwing up the courage to answer his reply, about replies other girls claim to have received. But none of them seem to have his book. No one answered my requests for a copy, and I haven’t come across a single post in which anyone, even the most avid of his fans, will admit to having read it.

Why? Maybe Bernardo’s fans are exercising more restraint than usual. Maybe the furor surrounding the book has dampened their curiosity a little (though it’s hard to imagine that anyone who would post, say, a homemade valentine commemorating Karla & Paul, would feel squeamish about a thriller). And maybe this reluctance on the part of Paul’s girls—and all the other bloggers and message board denizens who are openly obsessed with the case, even as they condemn Bernardo and Homolka as evil—comes less from a fear of what they will find than from a fear of what they won’t.

“Bernardo’s book is, it seems clear from the few reviews that have delved into its content, less the work of a criminal mastermind than of a posturing, illiterate child.”

Because Bernardo’s book is, it seems clear from the few reviews that have delved into its content, less the work of a criminal mastermind than of a posturing, illiterate child. “Have you ever cleaned out your dryer vent?” asks the Toronto Star’s Heather Mallick (who prefaced her review with the reassurance that she was able to download much of the book for free). “After careful stroking with a hand rake, one claws out a huge thicket of dry matted strands, a sort of felted matter. This is Bernardo’s brain, handy for oil spills or lining a bird’s nest but nothing more… He describes people the way a towel would, if towels could talk: ‘The five foot ten inch Abdel looked over at his one month older, but two inches shorter best friend Jared. Abdel said, “We are two poor, uneducated Yemenites, yet we have a boatload of cargo destined to change the course of world history.”’” The book, Mallick writes, is riddled with spelling errors and incorrect punctuation and turns of phrase that wouldn’t look out of place in a grade three composition: a driveway is “curved upward slopping,” a person immune to death is “innortal,” and the protagonist’s name is either Mason Steel or Mason Steale, depending on which page you’re reading.

It’s terrifying to realize that anyone could cause as much suffering as Paul Bernardo once did. It’s possible to take some comfort from the idea that he evaded the authorities for so long because he was some kind of devious genius. Harder to admit is that someone can destroy innocent lives and inflict fear on a whole generation while still having the mind of a child.

“Harder to admit is that someone can destroy innocent lives and inflict fear on a whole generation while still having the mind of a child.”

Paul Bernardo avoided detection first as the “Scarborough Rapist” and then as the “Schoolgirl Killer” not because he was clever but because he was lucky. When questioned in connection with the Scarborough rapes, he gave the police a DNA sample which then wasn’t tested for two full years, in part because the system was slow and in part because his status as a white, educated, middle-class professional placed him almost above suspicion. When Bernardo and Homolka abducted Kristen French in a St. Catharines parking lot and drove off in a gold Nissan, eyewitnesses recalled two men in a beige Camaro, which sparked a manhunt for the wrong kinds of suspects in the wrong kind of car. When Paul Bernardo’s home was searched following his arrest, police failed to find the tapes he had made of the assaults and captivities of Kristen French and Leslie Mahaffy—and his and Karla’s sexual assault of her younger sister, Tammy—not because he had hidden them ingeniously but because the police conducted a search so cursory that it failed to include the light fixture in which he had stashed the videos.

Hiding incriminating evidence in a light fixture is exactly the kind of thing someone would do in the movies, and for much of his life it seems Paul Bernardo made his decisions based on this principle. If he couldn’t have what he wanted, he would settle for illusion—or maybe he couldn’t tell the difference between the illusion and the real thing. He wanted to become a “big bad businessman” but didn’t want to put in the work to establish himself in his chosen career as an accountant, so he strove for the appearance of success instead. If he wanted to feel loved, he simply demanded someone—Karla Homolka, or, later, one of his victims—to tell them that they loved him.

“When we think of the psychopath, terrifying as he is, we can at least comfort ourselves with the belief that he is not a product of human society, but destruction made flesh. He isn’t hopelessly flummoxed at the prospect of constructing a coherent sentence”

When we think of the word “psychopath,” we often think of strength: of Hannibal Lecter and his brilliant schemes, his intellectual prowess, and his dry disregard for mere mortals (or “nortals,” as Paul Bernardo might put it). We don’t often think of weakness. It is hard to believe that weakness could cause such pain. We know weakness. We feel it. We identify it as human. We listen to the demands it makes on us, and sometimes we can’t control ourselves: sometimes we heed it, too. When we think of the psychopath, terrifying as he is, we can at least comfort ourselves with the belief that he is not a product of human society, but destruction made flesh. He isn’t hopelessly flummoxed at the prospect of constructing a coherent sentence. He doesn’t rent videos. Most importantly of all, if he has a favorite movie—if he even watches movies, somehow eschewing the more appropriate “evil” entertainment of, say, burning black candles and reading the Marquis de Sade en français—it certainly isn’t a Kevin Bacon vehicle.

Which brings us back to Criminal Law. When Paul Bernardo changed his name right before his 1993 arrest, he changed it to Paul Teale: an apparently characteristic misspelling of Kevin Bacon’s character’s name. After his arrest, friend of his and Homolka’s recalled Bernardo telling them: “One day, you’ll know all my secrets.” In Criminal Law, Martin Thiel tells his lawyer: “Someday, you’ll know all my secrets. I wonder if we’ll still be friends.”

Bernardo may have been fascinated by Martin Thiel, but the movie is really about his lawyer, Ben Chase. The movie begins with Ben successfully defending Martin against a murder charge, then realizing that Martin is, in fact, guilty—and has already struck again, murdering another young woman and masterfully disposing of any evidence that might link him to her death. Ben decides to take the law into his own hands, befriending Martin in the hopes that Ben might implicate himself.

Yet Martin, as sinister of a criminal mastermind as he is, seems to want Ben’s friendship more than anything else. He wants Ben to serve not just as his confessor, but as someone who will see the logic of his crimes, and adopt it as his own. “We really are partners now,” Martin says fondly, after Ben uncovers yet another of his crimes.

The movie ends with Martin weeping hysterically as he learns of Ben’s betrayal. Martin dies. Ben lives. And, watching this movie, you have to wonder what Paul Bernardo saw when he watched it—again and again and again. Where did he see himself? And where did he see his own partner, his own confidante, his own survivor? Thinking of Martin’s hysterical weeping, it’s hard not to think of Bernardo’s own hysterical weeping on the “suicide tape” he made for Karla after she left him. “Kar?” he calls, to no one. “Hey, Kar?” he whines. “Karla?” She always came to him before.

Did some of the power Bernardo had over Karla come not from his strength, but from his weakness? Did it come not just from physical and emotional abuse, but from Karla’s belief that he was really the weak one, and she the strong?

“Bernardo and Homolka’s union was not a once-in-a-lifetime event—two psychopaths crossing paths and leaving inevitable bloodshed in their wake—but something more mundane.”

If this is true, then it means that Bernardo and Homolka’s union was not a once-in-a-lifetime event—two psychopaths crossing paths and leaving inevitable bloodshed in their wake—but something more mundane. It means this dynamic can lead to destruction, even if it is rarely of the kind that makes headlines. It means his book is a danger to us not because it reveals him not as a formidable monster but as a monstrous child. And if this is true, then the book itself is well worth reading.

Criminal Law, like so many forgettable horror movies and thrillers, begins with every screenwriter’s favourite Nietzsche quote: “Whoever fights monsters should see to it that in the process he does not become a monster. And when you look long into the abyss, the abyss also looks into you.” If we believe the philosophy of Nietzsche—or at least the philosophy of Criminal Law—then this means we can’t study evil without risk becoming evil ourselves.

Yet believing Paul Bernardo’s novel is capable of spreading such a contagion means ascribing power to a man whose defining quality—whose only quality—was weakness. Acknowledging this weakness also means acknowledging that his words can’t hurt us. At their best, they might provide the kind of insight into Paul Bernardo’s psyche that can help us identify other Paul Bernardos before they cause as much pain and suffering as he did. At their worst, they are a mere curiosity. Hiding them from public sight makes them powerful, and makes Bernardo seem powerful by extension. It means giving him the kind of affirmation he so craved, and apparently always will.

SARAH MARSHALL is a PhD student at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Her writing has most recently appeared in The Believer, The New Republic, and The Best American Nonrequired Reading 2015.

LINDA BESNER talks to NYLA MATUK about her new book