Last Night a Critic Changed My Life

Zak Breckenridge on Joan Didion's impatience with programmatic thinking.

Welcome to the Partisan series "Last Night a Critic Changed My Life." Echoing a long-running feature in Mojo Magazine, which looks at life-changing records, this series will focus on moments when writers encountered the work of a critic and found themselves transformed.

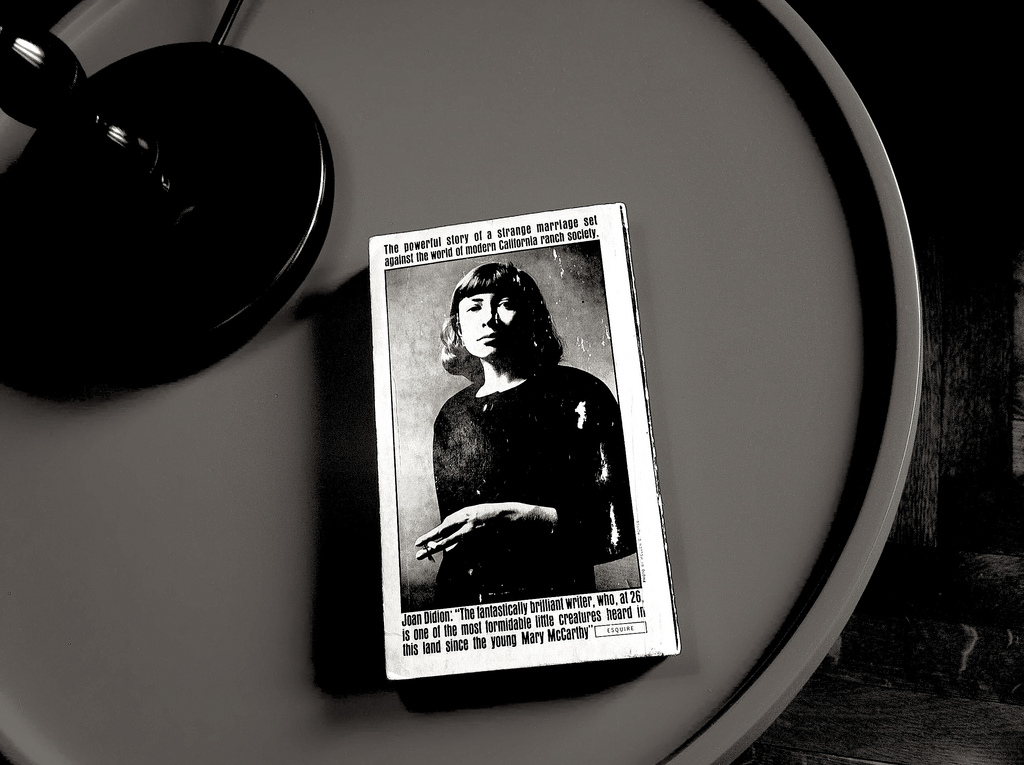

Photo Credit: Incase courtesy of Flickr/Creative Commons

I BEGAN READING Joan Didion ignorant of the culture war raging over her. However, I recently found out that to many, her place in our culture has been established, as if we already know what she had to say. All that’s left for the contemporary critic: decide whether or not you like Didion, and whether or not your identity matches your decision. And Didion, as both a writer and an icon, is all about image. The problem isn't really about the substance of her writing as much as what kind of person you are if you like her, or whether you can salvage your taste if you dislike her. These days we wear Didion more than we read her.

I knew none of this at first. I started reading her because I heard somewhere that she was one of a few American essayists who produced great work when they were young–her first collection appeared when she was thirty-three—and I kept reading for her wit, control of language, and insight about the landscape and culture of the West.

“The problem isn’t really about the substance of her writing as much as what kind of person you are if you like her”

I like to start at the beginning, so I began with 1968’s Slouching Towards Bethlehem. Here’s the first sentence of the first essay in that collection, “Some Dreamers of the Golden Dream”: “This is a story of love and death in the golden land, and begins with the country.” Didion will tell us first about the desert, the mountains, and the wind, then about who gets married there and what you can buy, then how you get there, which cheap motels you must drive past, then which fruit grow on the trees—all before we learn that her essay is about a murder trial. A few sentences indicate much of what is vital about Didion’s eye and style:

“It is the season of suicide and divorce and prickly dread, wherever the wind blows.”

“The future always looks good in the golden land, because no one remembers the past.”

“Here is the last stop for all those who come from somewhere else, for all those who drifted away from the cold and the past and the old ways.”

Didion’s California is a dream-world, but it is also a desert. Much of her best writing spans the imaginary and the environmental. How do hearts break in this hybrid land? How does human hubris deform the land?

Didion, I discovered, is more of an incisive critic than a journalist. She’s often dissatisfied with the subjects of her essays, and this dissatisfaction is knife-like—more scalpel than cleaver. “Pretty soon now, maybe next month, maybe later, Max and Sharon plan to leave for Africa or India, where they can live off the land,” Didion reports in the very famous essay “Slouching Towards Bethlehem.” She continues:

“I got this little trust fund, see,” Max says, “which is useful in that it tells cops and border patrols I’m O.K., but living off the land is the thing. You can get your high and get your dope in the city, O.K., but we gotta get out somewhere and live organically.” “Roots and things,” Sharon says… “You can eat them.”

A passage like this, drawn directly from her informants’ mouths, displays the emptiness and “atomization.” The essay offers a trenchant critique without any apparent commentary from the author. Journalism becomes a front for criticism.

“She’s often dissatisfied with the subjects of her essays, and this dissatisfaction is knife-like—more scalpel than cleaver. ”

In her 1971 Paris Review interview, Didion says that writing is “hostile in that...you’re trying to impose your idea. It’s hostile to try to wrench around someone else’s mind that way.” She claims the preface to her first essay collection that “writers are always selling somebody out.” This view of the violent potential of writing put me in mind of another author who has also been accused of aggression and pretension: the theorist Michel Foucault. “In speaking about [my subjects] I’m in the situation of the anatomist who performs an autopsy," he admits in a late interview. "With my writing I survey the body of others, I incise it, I lift integuments and skin, I try to find the organs and, in exposing the organs, reveal the site of the lesion...The venomous heart of things and men is, at bottom, what I have always tried to expose. I…understand why people experience my writing as a form of aggression.” There are many differences between Foucault and Didion, but the image of the writer as an anatomist helps me see the shape of her project. She is always after the venomous heart of an idea, a person, a movement. Like Foucault, like any good physician, she is also a historian. Lucille Miller, the main subject of “Some Dreamers of the Golden Dream,” does not exist without the dreamwork of Westward Expansion, nor does she exist without the Mojave, the Sierra Nevadas, and the Santa Ana wind.

Didion also cut into me, in a way. My intellectual upbringing before reading her had suggested that the Left was the only political camp that allowed for thinking at all. She validated many of my suspicions about liberal politics, and she gave me a choice beyond triumphalist progressivism and the steaming temper tantrum of American conservatism. Did others find her reactionary? For me, Didion has been a force of disruption and transformation.

IMAGINE MY SURPRISE then to find out that much of the literate American public is sick of Didion. They are sick of hearing about how perfect her sentences are. They are sick of her malaise and angst and “carefully described migraine[s].” But most of all they are sick of the image that Didion created, of the slim, neurasthenic, genius white woman writer zipping up and down the California coast in her white Corvette. (An image of which I was blissfully ignorant). As I learned more about her, I didn’t find any recent critical essays that didn’t mention Didion’s appearance in a Céline ad in early 2015. The poor woman “is a living stereotype” and “an established talisman of taste, an ideal entry in any catalogue of preferences.” Apparently, in this world-weary time we no longer read Didion; we display her, and, therefore, ourselves.

Though fashion has been at play in opinions about Didion since long before the Céline ad. Barbara Grizzutti Harrison begins her 1979 tirade against Didion with: “When I am asked why I do not find Joan Didion appealing, I am tempted to answer…that my charity does not naturally extend itself to someone whose lavender love seats match exactly the potted orchids on her mantel, someone who has porcelain elephant end tables, someone who has chosen to burden her daughter with the name Quintana Roo.” One of Harrison’s central criticisms of Didion as a writer (not just an interior decorator) is that she’s too focused on fashion: “The crime for which Didion indicts Lucille Maxwell Miller is of being tacky—of not, that is, being Didion.” Didion’s acolytes have been duped. They’re not enamored of a literary genius, they’re enamored of a brand. What may appear to be biting insight is nothing more than a set of parlor tricks. Didion the historian, the anatomist, becomes Didion the judgmental step-mother.

But if we excuse her by saying she was nonetheless a great writer, we have dodged the question by separating form from content. In fact, her supposedly immaculate sentences seemed to be the only thing critics could mention that didn’t have to do with her cult status or unseemly politics—in other words, the only thing that had to do with the writer’s writing. But this only serves to partition her arguments from the words they are presented in—an absurd mental contortion.

“Apparently, in this world-weary time we no longer read Didion; we display her, and, therefore, ourselves.”

IF DIDION HAS become a problem of fashion, it’s probably because she was regarded all along as a ‘literary’ writer, not a thinker. Critics have found in Didion a writer of consistent taste, affect, and aesthetic—never of thought. Her work may be “suffused with dread,” but it never convinces us that dread is a legitimate outlook. Her prose may ‘cut like a knife’ but we do not wonder whether or not the surgery was successful. This is most apparent in the reaction to her essay, “The Women’s Movement,” which was recently called “a bit of a sore point for a new, happily feminist generation of Didion lovers,” as if it were a tacky choice she once made for the red carpet.

It is not, as we might expect of a complaint about second-wave feminism, an essay about traditional values or protecting society. Instead, it's relentlessly concerned with ideas. This essay is awkward for contemporary readers because Didion seems to take the “wrong” position. She wrote against the women’s movement in 1972, only to have feminism triumph in the following decades (how embarrassing!). But instead of a reactionary humbug, we find a writer searching the movement in vain for any sign of intellectual integrity. “The creation of this revolutionary ‘class’ [women] was from the virtual beginning the ‘idea’ of the women’s movement," she writes in her opening paragraph, "and the tendency for popular discussion of the movement to center for so long around day care centers is yet another instance of that studied resistance to political ideas that characterizes our national life.” Her diagnosis is that the women's movement hastily adopted the "eccentric and quixotic passion" of Marxism, and just as quickly abandoned it for a rhetoric of self-actualization. Instead of thought she finds a “popular view of the movement as some kind of collective inchoate yearning for ‘fulfillment,’ or ‘self-expression.’” Didion charges "the so-called women’s movement" of the early 70s with steadily evacuating all ideas from its own political project.

She goes on to call the 'thinking' of this movement "Stalinist" because of "the coarsening of the moral imagination to which such social idealism so often leads. To believe in ‘the greater good’ is to operate, necessarily, in a kind of moral suspension.” Its claims are prescriptive rather than analytic, mandatory rather than reflective. And note how much force is packed into that phrase, “coarsening of the moral imagination,” which suggests that the political division into good and evil (radical and reactionary) is intellectually lazy, and that morality is a matter of "imagination" rather than law. And for clarity's sake, the phrase is bundled into a tactile metaphor, of coarse rather than fine morality. In contrast, she describes herself as "committed mainly to the exploration of moral distinctions and ambiguities.” This may not be a program for some better social revolution, but it shows the benefit of applying real thought to politics.

AND YET, UNFORGIVING as her critique is, she keeps it from swinging over into sexist reactionary bitterness by considering the pain and complexity of femininity itself. For her, the women's movement is an attempt to escape the fundamental wages of womanhood through social reform. “All one’s actual apprehension of what it is like to be a woman, the irreconcilable difference of it—that sense of living one’s deepest life underwater, that dark involvement with blood and birth and death—could now be declared invalid, unnecessary, one never felt it.” Even if the movement was originally aimed at social liberation, it’s now, Didion argues, aimed only at enabling escape from oneself. For her, the movement is dangerous because it has failed to understand the stakes of its own project.

Once you see this preoccupation in Didion, you notice how much of her work is devoted to the great contortions people undergo to avoid thinking. When she reports on the Center for the Study of Democratic Institutions (in the essay “California Dreaming”) she describes a place devoid of thought:

“Don’t make the mistake of sitting at the big table,” I was warned, sotto voce on my first visit to the center. “The talk there is pretty high-powered.”

“Is there any evidence that living in a violent age encourages violence?” someone was asking at the big table.

“That’s hard to measure.”

“I think it’s the Westerns on television.”

“I tend [pause] to agree.”

This is another instance of her ability to undermine her subjects by doing nothing more than quoting their own language, but this piece in particular is about how often the language of social importance is used to disguise hot air. In her own words, the Center is “the real souffle, the genuine American kitsch.”

So what seems to be a thematic of dread or relentless condescension is actually a deep impatience with people, movements, and texts that refuse to think. Perhaps acknowledging women’s involvement in “blood and birth and death” is not a program for a feminist political movement, but her essay is an example of incisive thought applied to politics. It cuts open the presumed unity and moral certitude of progressive politics, and invites other thoughts to fill the gap it opens. And her famously lauded style is an instrument of this thought. After all, how much could we expect of an anatomist with a blunt scalpel?

ZAK BRECKENRIDGE's work has recently appeared in Post-Road Magazine and is forthcoming in Colloquium Magazine. He lives in Chicago.

LINDA BESNER talks to NYLA MATUK about her new book