16 Things to Expect from the New Javier Marías Novel

Damian Tarnopolsky on Spain's best hope for a Nobel Prize

Javier Marías’s new novel, Thus Bad Begins, will soon appear in English. Here is what to expect from Spain’s foremost writer.

Javier Marías, photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

1. It will be about this: The novel will begin with Juan de Vere recalling the period in his youth when he worked as an assistant to Eduardo Muriel, a successful film director, in mid-1970s Spain. After the fall of Franco’s regime, with a tentative democracy in its place, Muriel asks Juan to look into the life of one of his friends, Jorge Van Vechten, a successful doctor who is rumoured to have blackmailed the wives and daughters of leftist families under the dictatorship. But as often happens in Marías’s world, the narrator’s investigation will get quickly thrown off kilter by his own secrets and desires, relating especially to Muriel’s wife, Beatriz Noguera. As de Vere and the reader are pulled further into a web of lies and betrayals, it will soon seem that no one can be trusted, as both love and forgiveness become equally arbitrary and inexplicable.

2. It will be in the first person. Voice matters in Marías, perhaps more than anything else. The Marías first person is possibly his greatest resource and greatest advance. The voice will be worldly, observant, highly perceptive, intelligent, highly self-aware. And then oddly lyrical, and oddly self-undermining, with its long sentences, extended by commas, correcting themselves, and ending in self-undermining disclaimers. This is his music: it is subtler and less extreme than Thomas Bernhard’s, more present in the world than Samuel Beckett’s, funnier and more vivid than W.G. Sebald’s. And yet, because of its occasional claustrophobic intensity, it does seem at times to veer close to a kind of madness. You may start wondering, after a while: how trustworthy is this very charming, very seductive person who is telling me these stories? Where have I been for the last few hours, listening to him? Am I in the hands of a madman? One chapter in Tomorrow in the Battle Think on Me (1994) makes it somehow reasonable for the narrator not to be sure if the prostitute he has picked up is in fact his wife, whom he recently split up from – a totally unreasonable hypothesis that Marías makes hypnotically possible to the reader. He spools it out (it’s so dark, but it looks like her), objects to it, (it’s absurd, I would know at once) and returns to it as if caught (but what if it is, she has that wilder side, and her voice, I don’t know everything about her), making it seem as if knowledge and desire might be darkly connected, equally powerful, equally worth doubting.

Spanish sentences often go on longer than English ones, so Marías’s connected phrases are a little less baroque in Spanish than they are in translation, but even in Spanish the sentences are noticeably extended, noticeably connected, and this style is philosophically meaningful, Michael Kerrigan says: “This isn’t the kind of confident narrative that nails down facts, causality and conclusions, but one that feels its way in constant uncertainty and self-questioning.” It is a thinking voice, a reading voice, a voice obsessed by events and by books, by words and by people, and by the act of narration itself. If you find this sinuous, questioning quality appealing, you’ll follow Marías through anything, I feel; if it doesn’t appeal to you, his work will remain closed.

3. It will be highly plotted: Marías’s novels tend to start with an astonishingly suspenseful or dramatic opening scene. In A Heart So White (1992) a woman walks away from a family lunch and shoots herself. At the start of Tomorrow in the Battle Think on Me a couple are just beginning a first adulterous embrace when the woman dies, leaving the man stuck in her apartment with her sleeping two-year-old son. These initial encounters often lead into an exploration of a dark family or romantic secret, but one that is prosecuted in and on-and-off way. At the end of the novel, everything will come together in a revelation of secrets that is as breathless and spellbinding as the best suspense novel. The past matters, the past returns. Or as Hamlet puts it, “Foul deeds will rise, though all the earth o’erwhelm them, to men’s eyes.”

4. While it will start by appearing to be plot driven, it will take some mysterious detours: One of Marías’s more unusual novelistic techniques - which helps him get away from too claustrophobic a first person voice, or allow the exigencies of plot to overwhelm his other interests - is to stop, turn around, explore something else. It’s hard to explain why this works so well. On the one hand the plot, the secrets, the investigation, develop, step by step. But, in between these steps, sometimes it almost seems in alternating chapters, there are bizarre subplots, or scenes that seem to have no connection to the main plot at all. Rather they have apparently thematic or psychological or humorous significance; they’re often darkly funny or slightly surreal or playful or otherwise somehow excessive or extraneous. In A Heart So White an interpreter deliberately mistranslates the words of the British Prime Minister in order, in part, to impress a woman (although also for fun, and for no good reason). In Tomorrow in the Battle think of Me several pages are taken up with the spectacle of an old man awkwardly trying to tie his shoelace. All Souls (1989) features long discussions of the narrator’s relationship to his garbage can. And yet sometimes, mostly, these divagations are not irrelevant at all. Over time, most everything connects – a prior event is overlaced by a new one, the past interweaves with the present– and more than one of Marías’s novels ends in a haunting series of echoes and repetitions. Still, the detours have a hypnotic quality of their own quite apart from any relationship to plot. Reading it, you will not be sure if the excursus will become central. It’s structurally unusual, and it works brilliantly, doing a lot to give Marías’s novels their strange, unforgettable originality.

5. It will help Marías along to a Nobel Prize (but also be criticized as self-indulgent and pretentious).

6. It will have an enigmatic epigraph, to a woman, probably.

7. As is the case with many of Marías’s books, you won’t realize that the terrific title is in fact a quotation from Shakespeare: “A Heart so White” is a phrase from Macbeth. “Your Face Tomorrow” is taken from Henry IV. There’s a tradition of course of using stray bits of Shakespeare as titles, everything from The Sound and the Fury (august) to The Fault in Our Stars (grave but whimsical) to Where Eagles Dare (thrilling). Usually such titles are a kind of rubber-stamping that says that the work that follows has quality or fits into a tradition, and is then forgotten about. But Marías repeats his titles, paraphrases them, makes motifs of them, returns to them again and again, sometimes explicitly referring to their source (which, in passing, is a good way to quote Shakespeare in a novel without the reader feeling that a much better writer has just hovered into view). “Thus bad begins” is from Hamlet: the full couplet is “I must be cruel only to be kind; thus bad begins and worse remains behind.” Typically, there will be more to Marías’s interest in Shakespeare in this book than the title. The narrator of Thus Bad Begins is named Juan de Vere. This recalls Edward De Vere, the seventeenth earl of Oxford - the aristocrat who is sometimes presented as the “true” author of Shakespeare. Whether you think of them as lunatically obsessed literary conspiracy theorists or dogged investigators into the greatest cover up in literary history, Oxfordians fit Marías’s purposes and his cosmos and they are the type of people he’s interested in. The Dictionary of National Biography says (sad to note) that the family “de Vere” is supposed to derive its name from Ver, near Bayeux, rather than there being any connection to the Latin veritas (truth). But their cognizance, the DNB notes, was a blue boar (a pun on “verres,” Latin for boar), and there is a Blue Boar Street in Oxford, where Marías’s novel All Souls was set. These kinds of connections, interpretative connections between what’s written and what’s read and what’s known and remembered, arise endlessly, reading Marías.

8. Despite its literary allusiveness and high-cultural setting, there will be sex, adultery, secrets, betrayals, murder, bars, and cigarettes: all the things we like to read about. Marías’s books feature a lot of passion, a lot of loving, a lot of revelations and surprises. Because, while his novels take place in the mind rather than the world, they also take place in the body rather than in the world: the body that smokes, that eats, that fucks, that spits, that wants. In A Heart so White, for instance, the narrator is drawn into helping a friend make increasingly explicit videos to send to suitors via a dating agency. Death is never far away, and its cousin, sex, is recognized by Marías as a motivating factor in adult life in ways that are sometimes elided, these days, for all our prurience. It’s not just that his characters are sexually interested in each other. His novels explore the fuller apprehension that all our adult projects have a sexual component; that when we’re talking about knowing things, or hiding things, or advancing, or finding things out, or getting to the bottom of things, or winning or losing, we’re also thinking sexually. It’s not that everything the characters do in Marías’s novels is reducible to sex in a crude way, or that sex is all that exists. Rather, in his novels sex has a fundamentally explanatory, unignorable force, if you want to think about what human beings are.

9. There will be a gypsy or someone on the corner outside making noise as the narrator tries to work at his desk, and he’ll try to get rid of them somehow.

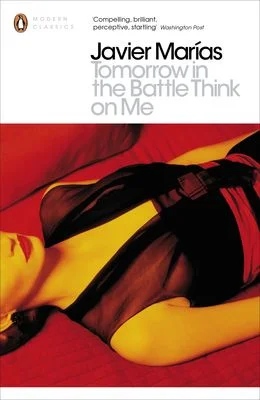

10. The book will have a better cover in the UK and US than in Spain.

11. It will be realistic, and not realistic. The settings will be recognizable. In spite of the intensity of the first person voice, in spite of the passing sensation that Marías’s novels all take place only in a refined and detached literary mind, in fact it will be grounded in the real world. Marías gives real street addresses and you can follow the movements of his characters around Madrid or London or New York on Google maps. You could walk in their paths if you live in one of these cities. And yet the novel won’t harp on physical detail or use it as a shortcut to characterization; it will eschew such observations as noting the way the character holds a wine glass tightly to show you how highly strung she is, etc. Similarly, it won’t seek to depict all of life. It will not seek to move through huge slices of society, historical periods, or settings outside Marías’s urbane Europe and North America. It will not feature children much at all (as fully realized people), nor animals, nor the furniture of daily life: plumbing, software updates, etc. A minimum of realistic detail will provide the stage, but it won’t do much work to convey character or serve to move plot along. There might be a gun on the wall in the first act but it won’t be fired in the third. Rather than creating a physically tangible world in which the characters can grasp and desire, the environment will characterize the mental and personal setting. I mean, real things impinge on the narrator, from the beggar on the corner to the store he remembers going to as a child because he loved the girl who worked there. It happens in the world but it’s experienced in the mind, and that’s where it matters.

12. It will mix reality and fiction: Javier Marías worked as a lecturer in Spanish Literature at Oxford University; All Souls is narrated by a lecturer in Spanish Literature at Oxford University. Marías claimed that the novel was not a roman a clef, but he was later moved to write another book, The Dark Back of Time (1998), as a response to all the readers who insisted that it was because they found themselves depicted in it. Marías’s afterword to All Souls notes that while the novel is fiction, many passages had antecedents in letters he had sent his friends when he was living in Oxford, in a house shaped like a pyramid (like the narrator of All Souls). The terms reality and fiction aren’t quite mobile enough to do credit to what Marías does in his writing.

In one of the most moving, haunting and memorable passages in All Souls, the narrator’s hypothetical connection between a forgotten (real-life) author known pseudonymously as John Gawsworth and a tragic story from his (the narrator’s) lover’s past. Gawsworth inherited the throne of the Kingdom of Redonda, a Caribbean micro-nation originally claimed (it seems) by the father of the writer M. P. Shiel, the novel has explained in one of its eccentric divagations. But after All Souls was published, the real king of Redonda at the time was so moved by the novel’s depiction of Gawsworth that he abdicated in favour of Marías himself in 1990, and Marías has continued the Redondan royal tradition of ennobling people he likes, from Orhan Pamuk to Pierre Bourdieu. He also created a literary prize, judged by the Redondan aristocracy, the winner of which is named a duke or duchess.

Marías shares many things with postmodern writers who make the status of their fictional works uncertain, from John Fowles to Italo Calvino (not to mention such predecessors as Laurence Sterne and Miguel de Cervantes) but there are significant and interesting differences too, that make his work more complex, thoroughgoing and human. In his afterword to All Souls, Marías notes that he and his narrator are very similar - they even share a birthday. The key difference between himself and his narrator is that the narrator, looking back on his time in Oxford, now has a wife and son, something Marías lacks. This is a better way to differentiate them, he says, than by giving the narrator a different background or a different birthday than the author, because the real Marías could not have a different background or a different birthday. But he could have a wife and son. The narrator, like any fictional narrator, is someone the author could have been; could yet be, even. In this way, Marías argues, he makes a theme out of something essential to the art of the novel. More than mixing the real and the fictional, Marías’s mode underscores that what matters about literature is its potential quality. Fiction is about, is complicit with, is tied to what might happen, what might have happened, more than to what did happen, Marías writes. This is why it matters, he claims: because what might-have-been is as significant a part of our lives as what we are. We are haunted, and animated, by the words we didn’t utter, the job we didn’t get, the lover we didn’t marry. And this is what makes Marías’s work -with its potential, might have been, could be quality- so haunting, and so animating.

13. It will repeat itself. Marías’s narrators like, for example, to go through all the possible versions of what might have happened after he made that telephone call, give it in detail, give the alternate version in detail, hypothesize about other possibilities. It will repeat characters and motifs from Marías’s other works, enhancing the sense that he is creating a literary universe of his own. The novel itself will keep to a close degree to the formula outlined here. It’s a repetitive formula in a different way: it will repeat phrases and scenes. Long sentences will turn and turn about the same point, not quite able to move on. More unusually, entire paragraphs of description, stated early in the novel, will return later verbatim. The narrator will be an obsessive repeater, returning to key phrases and quotations. The British writer Jonathan Coe argues that repetition in Marías is connected to his view of character: people don’t learn or change; we’re locked in patterns of thought and behaviour, regrettably enough. But of course, the second time something happens, it’s different from the first time, simply because there has been a first time. This is part of what makes Marías’s repetitions moving and intriguing; even while it repeats itself, repetition suggests the “what might have been” that so intrigues Marías. This is happening again: it might have been different.

14. It may feature American films and English writers but it will in all likelihood make no reference to anything Canadian. Although Alice Munro won the Kingdom of Redonda literary prize in 2005, and gained the title “Duchess of Ontario” accordingly.

15. It will compare, at some point, the colour of a character’s eyes to the colour of an alcoholic drink.

16. It will end with a long talk in which a devastating secret is revealed, perhaps overheard or accidentally, usually to do with love, usually to do with a woman’s death: Themes and icons will return, recalibrated. At the same time this will be somewhat exaggerated, almost as if the novel is making a joke out of the idea that the ending is the point at which themes and subplots return and get neatly tied up. The paragraphs will become longer, studded with repetitive motifs and quotes and repetitions in brackets alluding to earlier moments. Though we will know what to expect, though we know it is ending in the way novels are supposed to, though we recognize that it is ending the way Marías’s novels always end, we will still be affected, because we always are. The music will grow and you’ll read faster, longing to find out, desperately moved. You’ll find the collaging haunting and intelligent; you’ll find the experience of reading Marías to be unmatched by anything else in contemporary literature, except perhaps for his works to come.

DAMIAN TARNOPOLSKY is the author of the novel Goya’s Dog and an editor at Slingsby and Dixon. His articles and reviews have recently appeared in The Globe and Mail, the Literary Review of Canada, the University of Toronto Quarterly, and elsewhere.

WHAT TO READ NEXT: 15 REASONS YOU SHOULD BE READING DON COLES'S A SERIOUS CALL

LINDA BESNER talks to NYLA MATUK about her new book