The Only and Original

How Billy West nearly out-Chaplined Chaplin

by Will Sloan

IN 1917, FOUR years after he arrived in Hollywood, Charlie Chaplin built his own studio at Sunset Boulevard and La Brea Avenue. The five-acre property, where Chaplin would make all his films and employ a full-time staff for the next 35 years, was one of the perks of a contract unprecedented in the history of entertainment. In his new deal with the First National Exhibitors’ Circuit, Chaplin was guaranteed $1 million for eight films, with complete creative control, half the profits, ownership of his work after five years, and a personal studio that would become his kingdom. It was the culmination of a short period in which he went from a small-time vaudevillian to a cultural icon–his films massively popular around the world, and his “Little Tramp” character the subject of toys, books, comic strips, costumes, and songs.

At 1329 Gordon Street, a mile and a half east from the Chaplin Studio, another comedian briefly carved a niche as Chaplin’s best impersonator. Chaplin’s new contract gave him the luxury to be a perfectionist, and when he slowed his output, the demand for his films stayed high. Billy West was there to fill the void.

Chaplin’s films included Dough and Dynamite, The Tramp, A Night Out, His Trysting Place, The Champion, and The Count; Billy West’s included Dough Nuts, The Hobo, His Day Out, His Married Life, The Hero, and The Millionaire. Chaplin labored over films for months; Billy West pumped out a two-reel comedy every other week, juggling multiple productions at once. Chaplin took an interest in music, composing and publishing pieces for the cello; Billy West released a series of waltzes. West’s crew was dotted with former Chaplin collaborators, including gag writers (Vincent P. Bryan, Chuck Reisner) and co-stars (Leo White, Mack Swain). He emulated Chaplin so carefully that he slept with his hair in curlers and learned left-handed violin.

Billy West copied Chaplin shamelessly but skillfully: there were other Chaplin imitators, but only West could sell his films on the strength of his own name. “His work is so strikingly clever and original,” stated a cheeky publicity blurb, “that he fears no comparison with any other performer now on the screen.” According to studio publicity, Billy West was “the Funniest Man on Earth.” In 1918, Chaplin released only three short films; the same year, Billy West starred in 15. West was more than just a clone: he aimed to out-Chaplin Chaplin.

“West was more than just a clone: he aimed to out-Chaplin Chaplin.”

A CENTURY AFTER his rise to stardom, Chaplin’s rags-to-riches story has taken on the dimensions of a folk tale. Born in London in 1889 to a pair of minor music hall stars, Charlie fell into poverty when his estranged father drank himself to death, and his mother lost her voice, then her mind. As she drifted in and out of institutions, Charlie and brother Sydney spent time in orphanages and workhouses, rising from hardship through vaudeville. Charlie’s big break came at age 19, when Sydney introduced him to the Fred Karno Company, where he honed his skills as a comedian and acrobat. The troupe toured America, where Chaplin’s performance as a comical drunk impressed Mack Sennett, president of the Keystone Film Company. In September 1913, Chaplin joined Keystone as a comedian for $150 per week (much more than he earned in vaudeville), and made his first film in January 1914. “A year at that racket,” wrote Chaplin in his 1964 autobiography, “and I could return to vaudeville an international star.”

If studio publicity is to be believed, Billy West had a turbulent backstory of his own. Born Roy B. Weissburg in Russia in 1882, his earliest memory was allegedly watching his aunt murdered in front of him. This incident is left frustratingly vague in surviving publicity material, which also asserts that he fled to the United States via London, studied medicine (presumably at a grade-school level), and considered a career in aviation (“One flight cured him of all ambitions,” said Motion Picture News). Whatever the truth, he was educated in Chicago, but quit school around 1909, and supported himself as a full-time singer, comedian, and cartoonist.

Like West, Chaplin began his film career as an imitator of sorts. Sennett hired him as a replacement for Keystone’s departing star Ford Sterling, and in Making a Living (1914), Chaplin’s overcoat, top hat, droopy facial hair, and hammy acting follow the Sterling template. For his second film, Chaplin went to the Keystone wardrobe and quickly threw together what would become the most famous costume in film history: tight jacket, baggy pants, derby hat, trick cane, and toothbrush mustache (big enough to make him look older, but small enough not to hide his facial expressions). “By the time I walked on to the stage he was fully born,” Chaplin claimed in his autobiography. He recalled telling Sennett:

“You know, this fellow is many-sided, a tramp, a gentleman, a poet, a dreamer, a lonely fellow, always hopeful of romance and adventure. He would have you believe he is a scientist, a musician, a duke, a polo-player. However, he is not above picking up cigarette-butts or robbing a baby of its candy. And, of course, if the occasion warrants it, he will kick a lady in the rear–but only in extreme anger!”

In reality, the Tramp took a while to come into focus. In early films like Mabel’s Strange Predicament and The Property Man, he’s distinctly unlikable, and the humour comes from his drunkenness, lechery, and violence. Chaplin also tried other characters, appearing as a Keystone Kop in The Thief Catcher, in full drag as a jealous wife in A Busy Day, and shockingly boyish sans mustache in Tango Tangles. These performances–full of grimacing, eye rolling, and faux-melodramatic mugging–conformed to the Keystone house style. Chaplin worked with other directors on these films, and feuded with them all. When Sennett let Chaplin direct himself, his acting grew subtler.

“Everyone thinks they can do a Chaplin impersonation–the cane twirling, the crooked feet–but even Chaplin might have been unconscious of some of the mannerisms West captured.”

By the end of 1914, Chaplin was the most popular comedian on the Keystone lot. While his costume and mannerisms were essentially set, his directorial style would undergo a drastic evolution: at the Essanay Studios from 1915-16, and the Mutual Film Corporation from 1916-17, he would experiment with combining comedy and pathos. “Naturalness is the greatest requisite of comedy,” he told Motion Picture Magazine in 1915. “Real things appeal to the people far quicker than the grotesque. My comedy is actual life, with the slightest twist or exaggeration.” The bittersweet ending of The Tramp (1915) was a key moment: after failing to “get the girl,” Charlie walks dejectedly along a dirty road away from the camera. Suddenly, he perks up and saunters into the horizon, ready to face a new day.

Because Chaplin’s comedy appealed across age and class, and because his silent films could be exported around the world, he achieved fame at an unheard-of speed and scale. When Chaplin’s popularity exploded, Billy West was living in Chicago, where he tried out a Chaplin imitation at a local parade. It was a hit, and West took it on tour in vaudeville. In 1916, a pair of Chicago lawyers hired West to star in a Chaplinesque comedy they were funding, which they sold (along with West’s contract) to the fledgling Unicorn Film Corporation. Ike Schlank, the Unicorn president, announced to Moving Picture World that he had discovered “a new comedian who is entirely different in rank and file from the screen fun-makers.” According to studio publicity, “While Billy West bears a striking resemblance to a certain famous comedian of the films, at the same time his methods are so original that the pictures in which he appears mark a distinctly new epoch to the screen.”

"The Hobo", 1917, starring Oliver Hardy and Billy West, directed by Arvid E. Gillstrom and produced by Louis Burstein

Early in The Hobo (1917), a tramp wakes up on a cargo train where he has spent the night. He yawns like Charlie, files his nails like Charlie, bobs his head like Charlie, and whistles like Charlie. When the conductor spots him and forces him on his way, the tramp tips his hat and flashes a big smile–squinty eyes, toothy grin–just like Charlie. And, before he goes, he dusts the conductor’s baton, swipes his cigarette, takes a puff, blows smoke, puts the cigarette back, tips his hat, and waddles off. Everyone thinks they can do a Chaplin impersonation–the cane twirling, the crooked feet–but even Chaplin might have been unconscious of some of the mannerisms West captured.

“West understood that the Tramp was more than just a tramp.”

West knew how to perform a Chaplin-style gag, like a small, wonderful moment when he’s being chased by two cops in His Day Out (1918): the officers leap towards him from opposite sides, he ducks, and as they smash into each other, he slips between their legs. His films picked up on recurring Chaplin motifs, like the Tramp’s constant run-ins with the police, and his relentless deployment of kicks to the backside. But what really separated West from the other faux-Chaplins can be seen in that encounter with the conductor; he captured the Tramp’s gentlemanly pretensions, and the way he clings to his dignity in even the most degraded circumstances. West understood that the Tramp was more than just a tramp.

This set him apart from the imitators who played the character as a generic goof. There was the string of doubles (Harry Mann, Monty Banks) that West’s company would eventually use to replace him. There was Ray Hughes, who film historians say impersonated Billy West as much as Chaplin. There were European clones like “Monsieur Jack” (André Séchan) and “Charlie Kaplin” (Ernst Bosser). There was Carlos Amador, a Mexican comic who was billed as “Charlie Aplin” in The Race Track (1916), a remake of Chaplin’s Kid Auto Races at Venice. Chaplin won an injunction against the film, but Amador argued that the Tramp’s clothing was in the public domain. The case was finally resolved in 1925, when the Superior Court of California ruled that The Race Track was “a fraudulent scheme and conspiracy.”

Some of Chaplin’s old colleagues from the Karno Company got in on the act. Stan Laurel, briefly his roommate, toured America in a show called “The Keystone Trio” (he played Chaplin alongside lookalikes of comedians Chester Conklin and Mabel Normand). Billie Ritchie, who once played the Drunk in the Karno shows, claimed to have invented the Tramp, and parlayed this into several Chaplin knockoff movies. (When Ritchie died in 1921, Chaplin took pity enough to hire his widow for the studio wardrobe department.) Chaplin’s popularity was so total that the Tramp’s broad strokes, if not his particulars, influenced a generation of comedians. Before Harold Lloyd became Chaplin’s biggest box office rival in the ‘20s, he tried a character called “Lonesome Luke,” whose outfit was just different enough from the Tramp to avoid plagiarism. Sydney Chaplin, who preceded Charlie in vaudeville by several years, was his brother’s replacement at Keystone, where his character “Gussle” bore a more-than-passing family resemblance.

“Chaplin’s popularity was so total that the Tramp’s broad strokes, if not his particulars, influenced a generation of comedians.”

These are some of the higher-profile clones, but many other small and amateur companies made “new” films using old footage and imitators. Few of Chaplin’s films for Keystone were registered for copyright, making them safe for retitling, re-cutting, and piracy. In November 1915, the Essanay Film Company, where Chaplin worked, placed a full-page “Appeal for Fair Play” in Moving Picture World. The open letter referenced “letters of protest received from numerous exhibitors who secured from so-called film exchanges” such “patched-up films” as The Mix-Up, Ambition, and The Revue. Ironically, Essanay would eventually make several hodgepodges from outtakes and stock footage (Chase Me Charlie, The Essanay-Chaplin Revue of 1916, Triple Trouble) after Chaplin’s departure.

The “patched-up films” became so prevalent that under his Million Dollar Contract for First National, Chaplin had to sign his name under his films’ title cards to certify authenticity. Still, the demand for these bootleg films increased as Chaplin’s output dwindled, from 15 films in 1915 to just two in 1919 (Sunnyside and A Day’s Pleasure – both of which were coolly received). In 1920, during the yearlong production of The Kid, an article in Photoplay called “A Letter to a Genius” pleaded to Chaplin: “We are not commanding nor advising nor even criticizing; we speak because we need you – because you made this turbulent God’s marble a better thing to live on – because since you have been out of sorts the world has gone lame and happiness has moved away. Come back, Charlie!” A case could be made that, during the long months between new Chaplin films, these bootlegs helped keep him in the public eye.

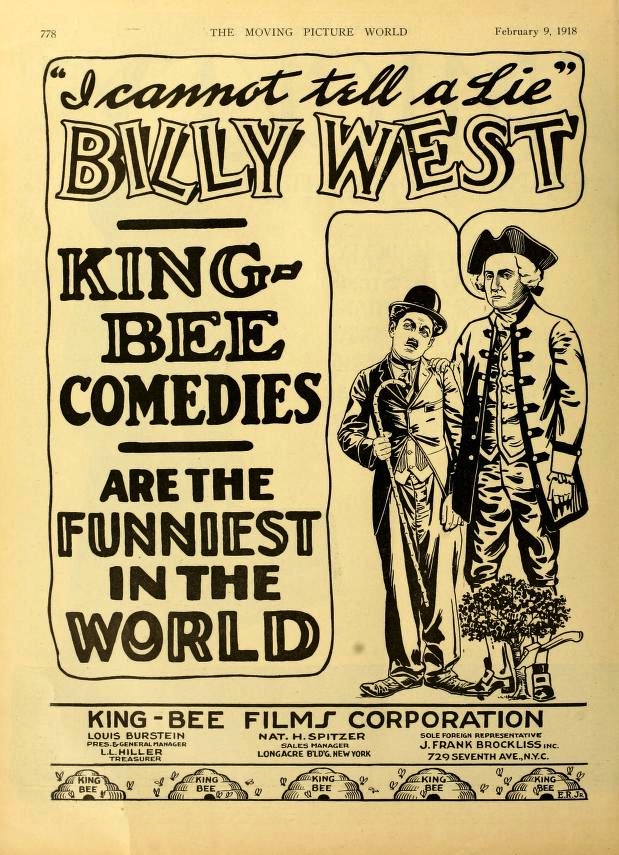

WHEN THE UNICORN Corporation went bankrupt, Billy West’s contract went to King-Bee, a B-level company that sold films on a state-by-state basis. A May 1917 Variety review of West’s first King-Bee efforts said, “Both abound in rough comedy material and from general appearance should prove laugh-provokers in the houses which cannot afford to get the new Chaplins.” Indeed, the films were surprisingly successful, first in rural/suburban markets and eventually the big cities. “Our patrons like Billy West and we are not missing the Chaplin comedies since we have started these,” wrote one Chicago theatre owner in Motography.

These positive notices aside, West was generally dismissed in the trade papers. When West started composing music, a Film Fun columnist wrote, “Billy West has written a waltz! Wouldn’t that strangle your baby grand? Can it be the title is, ‘I Use Ev’rything of Chaplin’s But His Brain’?” When King-Bee made the questionable decision to publicize a love letter from a Japanese fan, Photoplay wrote: “Perhaps this was such an event in the life of this shameless imitator of Chaplin that it was considered worth recording publicly. It is the first case on record, so far as we know where any actor has been such a cad.” A humor columnist for Picture Play suggesting appointing West as “ambassador to Ujiboji, which is the farthermost island of the Fijis. No one ever returns from Ujiboji.” Some papers printed his name entirely in lower-case.

“In his films as writer-director, Chaplin resorted to race-based humor exactly once, in A Day’s Pleasure (1919), in which a black jazz band turns white from seasickness.”

In response to such contempt, King-Bee tended to emphasize West’s extraordinary work ethic. “There is no break between pictures at the King-Bee studios,” wrote Ed Rosenbaum Jr., the studio publicist. “A picture that shows the funny Billy West in a sanitarium was finished one day at 12 noon, and at one o’clock he was in a pugilistic comedy that promises to be a knockout.” Studio manager Nat Spitzer told Motion Picture World that the studio housed enough sets so that when filming two movies simultaneously, “Billy, inasmuch as it is not necessary for him to change his costume, can simply walk from one scene into the other and keep the two scripts going at once.”

These working conditions could explain the general hackiness of a lot of West’s films. Consider a regrettable gag from The Hobo: While working at the train station, Billy meets a blackface man and his overweight wife, receive a crate marked “Handle with Care.” When they open it, the couple’s nine children emerge. Billy gives the family a watermelon, and the camera lingers on the cheery bunch eating it on the curb. In his films as writer-director, Chaplin resorted to race-based humor exactly once, in A Day’s Pleasure (1919), in which a black jazz band turns white from seasickness. This film, cobbled together to satisfy his distributors during the long production of The Kid, came at a self-admitted personal low-ebb. Otherwise, he took pride in avoiding such material.

Conditions could hardly have been rewarding for West, who was approaching his tenth anniversary as a comedian and must have aspired to more than copying someone else. He might have looked forward to a five-reel feature that King-Bee announced in the trades–a version of the King Solomon story called Old King Sol–but the film was cancelled, and he continued to churn out shorts at a punishing rate. A notice in Variety in June 1918 mentioned that West had made 25 comedies since 1916 without any vacation. This workload–which would have also included hours of watching and re-watching Chaplin’s films–couldn’t have made the beatings from the press any easier.

This might be why in 1919, three months after signing a four-year contract with the Bull’s Eye Film Corporation (which absorbed King-Bee), West defected to join the Emerald Motion Picture Company. An announcement in Exhibitor’s Herald said that Emerald would distribute 24 new comedies from the newly formed Billy West productions, with West acting as his own producer/director. To the press, Emerald president Frederick J. Ireland addressed West’s earlier work apologetically:

“Mr. West, in the past, has proven the hold he has upon the hearts of the public. His artistic talent has been fully recognized, and I do not profess to be able to improve his artistry, but after seeing a number of pictures in which Mr. West was presented, I was convinced that he was never given the right embellishments or ensemble to justify his clever work. The shadow of cheapness and rush was always evident. In producing pictures with Billy West as the star, the cost of production will be given no consideration by the Emerald Company. The very best in players and production is our aim.”

Bull’s Eye struck back with a two-page ad in Exhibitor’s Herald, claiming it owned not only Billy West’s services, but also his name. Bull’s Eye sought an injunction against Emerald’s films, and warned theatre owners that when the case came to trial, exhibitors using the “Billy West” name without permission could face prosecution. In the meantime, Bull’s Eye continued producing its own “Billy West” comedies, with comedian Harry Mann impersonating Billy West impersonating Charlie Chaplin. Though Emerald’s publicity announced that he was a “magnet of the screen” and “America’s own comedian,” West now fought the injunction by testifying to his own mediocrity. He presented the court with affidavits from exhibitors who cancelled their contracts, and according to Exhibitor’s Herald:

“The defendant, further answering, expressly denies that he has certain unique and peculiar characteristics as comedian and denies that these peculiarities are well known to the motion picture trade, and to the people who attend motion picture theatres and denies further that a great many people go to motion picture theatres when they see a Billy West comedy advertised; and answering, further, denies that his humor appeals to a great many audiences.”

A few months earlier, West wrote the opposite in an open letter in Exhibitor’s Herald titled, “An Honest Declaration.” He stated that he severed relations with Bull’s Eye on February 16, 1919, and accused the company of trying to “willfully defraud the public” with their faux-West faux-Chaplins. The letter gives a sense of how he viewed himself:

“For ten years, I have worked earnestly and incessantly, both on stage and screen, to make my name a valuable trade-mark, and I do not intend to allow others to profit by my labor. I am now under contract to the Emerald Motion Picture Company to produce genuine Billy West Comedies, and I positively declare that no other company has right or title to my name.”

He signed it, “Yours for truth and fairness, the Only and Original, Billy West.”

CHAPLIN MATURED AS a filmmaker with The Immigrant (1917), his penultimate film for the Mutual Company. This simple, evocative two-reel short begins on a grimy trans-Atlantic steamship, where the Tramp is one of many poor immigrants en route to the United States. He meets a destitute woman and her sick mother, and, learning that they had been robbed, slips them his poker winnings. The film rejoins the Tramp weeks later, “hungry and broke” in an unfamiliar city. He finds a coin on the sidewalk and enters a café, where he again meets the woman. Her mother is now dead, and the Tramp offers to buy her a meal, but when the time comes to pay, realizes the coin fell through a hole in his pocket.

“The difference between Billy West and Charlie Chaplin may be difficult to articulate in the abstract, but readily apparent when you finally see the real thing. It’s the difference between talent and genius.”

Chaplin’s early attempts to meld comedy and sentiment were sometimes awkward and uncertain: the downbeat ending of, for example, The Bank (1915)–where the Tramp’s heroism and romance are revealed to be just a dream–strikes a jarring note after 20 minutes of raucous, violent slapstick. In The Immigrant, the sadness and the humor inform each other: the awfulness of the ship is funny until it isn’t anymore. Chaplin had known dire poverty, and was famous for playing a tramp, but with The Immigrant, he actually made being poor his subject. From this point on, it would become the greatest source of his comedy, and inform the string of masterpieces that followed. When the Tramp eats his boot in The Gold Rush, or tries to make a home out of a shack in Modern Times, one senses Chaplin harnessing the shame that traumatized him as a child.

Several of Billy West’s collaborators also graduated to remarkable success in the ‘20s. Charles Parrott, a director at King-Bee, became a major comedy star in the ‘20s under the name Charley Chase. Harry Cohn, who produced many of West’s later films, bought full ownership of Columbia Pictures, where he ruled as one of Hollywood’s most powerful moguls until his death in 1958. Oliver Hardy, the villain in many West films, saw his career as a journeyman actor transform when he was paired with Stan Laurel. Laurel & Hardy would become the most beloved comedy duo in film history.

As for West, Emerald won exclusive rights for his services after a bitterly contested lawsuit. Shortly after, Emerald and Bull’s Eye merged to form Reelcraft, where West was given his own unit–Billy West Productions–and allowed to inch away from the Chaplinesque persona. Produced and directed by West himself, these comedies now featured West wearing a straw hatted boulevardier, but with the same Chaplinesque toothbrush moustache. A handful of films followed, but the relationship with Reelcraft ended shortly after, and West returned to vaudeville.

Later in the ‘20s, West developed his own character in two separate series of comedies for Joan Film Sales and the Arrow Film Corporation: “Billy West will give himself plenty of time to perfect his work, as the comedies will be produced no faster than one month,” promised a 1920 article in Motion Picture News. “He will have plenty of time to perfect every foot of film, and the keynote of his comedies will be concentration on every detail.” West starred in these comedies as a dapper city slicker–trimmer moustache, more stylish clothes–and though no longer a Tramp clone, his costume was now derivative of a character created by Monty Banks, another onetime Chaplin imitator. He never rose from the second rung of silent comedians, and his popularity was never as high with his own character as it was when he played the Tramp.

West’s comedies continued until 1926 when he shifted to directing full time, briefly serving in Fox’s short film department until it merged with Movietone in 1928. As an actor, he took bit pars well into the ’30 (a reporter in It Happened One Night and a hobo in Hallelujah! I’m a Bum, to name two). He found steadier employment on the Columbia lot as an assistant director and, eventually, manager of the Columbia Grill restaurant. He died July 21, 1975, suffering a heart attack while leaving the Hollywood Park racetrack. Though he had long since faded into obscurity, West’s movies occasionally popped up under Chaplin’s name in film archives and the 8mm home movie market. Thanks to the Chaplin connection, more of his films survive than those of many of his more respected contemporaries.

In a 1919 Pictures and Picturegoer article titled, “Funniosities in Charlie’s Mail,” one of Chaplin’s most memorable letters came from a fan who said he would “enjoy it more if you would be yourself and not always be trying to imitate Billy West.” Writer Elsie Codd reported that Chaplin kept the letter “against the time when he notices symptoms of acquiring a swelled head.” The difference between Billy West and Charlie Chaplin may be difficult to articulate in the abstract, but readily apparent when you finally see the real thing. It’s the difference between talent and genius.

While Chaplin was litigious towards imitators and bootleggers, he never took legal action against Billy West. Though West and Chaplin made their movies within walking distance, the two comedians are said to have studiously avoided each other, but inevitably, they did cross paths at least once. In an interview with historian Kevin Brownlow, West’s unit manager Ben Berk said that Chaplin passed the Bull’s Eye crew one day while they were filming in the street. According to Berk, Chaplin paused to give his greatest doppelganger a measure of praise: “You’re a damned good imitator.”

WILL SLOAN has written for NPR, The Believer, Hazlitt, and Maisonneuve.