Biographies Are Too Big

As he embarks on a new biography of Graham Greene, Richard Greene (no relation) declares war on the dreariness of details

A librarian in Texas once called me a “re-peat customer.” That was at the Harry Ransom Center, the great manuscript repository in Austin. In 1925, the State gave the University of Texas an oil field. Unsurprisingly, things have gone well ever since. When famous authors sold their papers at auction forty or fifty years ago, the Texans were there buying up the best of them. “Gone to Texas” became a catch-phrase among auctioneers. It’s less of a monopoly now, but the Ransom Center is still buying. Last year, Ian McEwan pocketed two million dollars for his manuscripts and emails.

The money-for-manuscripts business alarms some people, particularly in the UK, who see their patrimony going abroad. This is an understandable position, even if British museums are full of artifacts looted from other countries. (A director of the Ransom Center once pointed to the Elgin Marbles as an example of this sanctimonious double-standard.) And for ageing authors, many of whom have spent most of their lives broke, the sale of papers provides a little late affluence—giving papers gratis to the Bodleian might be patriotic, but it would also be stupid. Nowadays, many important collections from all over the world still make their way to Texas. Go west, old manuscript.

I spend some part of every summer in Austin’s 100 degree heat. It all started in 1993, when I was trying to put together a volume of Edith Sitwell’s letters. I have gone on to other projects, a biography of Sitwell, and a volume of Graham Greene’s letters. I’m now working on a book to be called, tentatively, Involvements: The Life of Graham Greene. It’s an odd thing to have acquired a parenthesis after one’s name, but I’m usually referred to by reviewers as "Richard Greene (no relation)." It's as if my own family tree had been stricken with Dutch elm disease.

I’m the sort of fellow who can be corrupted by the riches of Austin. If as a child you wanted to be a detective but shied away from soft-nosed bullets (incoming), then literary biography is a good alternative career. You get to interrogate witnesses, peer in through windows, and, as my wife once observed, read other people’s mail. The worst that can happen: you attract a libel suit, or find yourself reported to a gossip columnist for not mentioning your subject’s distant and temporarily surviving relatives in the book. (The latter happened to me.)

In Austin there’s so much evidence for the literary biographer that you can stop picking and choosing. You can dump all sorts of Facts into your mind’s pick-up truck and be gone. Back home, as you begin writing, every detail of your research becomes precious. You treasure all the clues pertaining to your subject’s missed dinner parties and cancelled dental appointments—the bits you gathered in your days as literary gumshoe. It is at that point, you email your publisher a bright idea: “This should be a multi-volume work.”

“Fat biographies no one has read are treated with an entirely bogus reverence.”

As archives have grown deeper, books have grown longer. In the sixties, Clive James, pushing around a recently published biography of Ford Madox Ford on a handcart, diagnosed an outbreak of “giganticism” or “elephantiasis.” He knew that most reviewers would never read books of enormous length and would seek a hopefully benign alternative: “The immediate temptation is to hail a masterpiece.” And so fat biographies no one has read are treated with an entirely bogus reverence. Stuart Kelly writes, “The biographer becomes a glutton of fact and anecdote, a sybarite delighting in the toothsome tale no other connoisseur of the field has tasted…. the tendency has always been towards microscopic detail and consequently maximal length.” James and Kelly are right.

Norman Sherry worked for about thirty years on an authorized three-volume life of Graham Greene and lost his way in a thicket of obsessions: he filled a quarter of his first volume with quotations of Greene’s infantile love letters to his future wife and with accounts of obscure transactions with hookers. In the second, it seemed that Sherry had fallen in love with Greene’s deceased mistress Catherine Walston, the model for Sarah Miles in The End of the Affair. In the third volume, he introduced snippets of his own poetry into the generally morbid text, and was reduced to meditating on the decay of Greene’s body into “human jam.” Throughout the whole work, the plots of extremely well-known novels are summarized at great length. Sherry even grew dissatisfied with normal methods of research and consulted a fortune teller about his subject. In the end, Sherry lost all perspective about Graham Greene. He told a reporter: "I often felt I must be him, I lived within him."

After years of being annoyed by Sherry and his shenanigans, I now feel a certain sadness for him. I don’t believe in definitive biographies—new evidence can come to light at any moment and overthrow much that seemed certain. You can do your best over decades of research and still produce nothing more than an interim report. The ambition to do more is slightly crazed.

“More tiny facts do not mean more truth, whatever a positivist might say.”

And yet I click on all the folders of notes on my hard drive. I try to count the thousands of scanned documents, and ask, what next? Beyond a certain point, more pages in a biography can equate to intellectual diminishment. Narrative is constantly laid aside in favour of the curious detail; the development of themes is sacrificed to a love of minutiae. For example, how do dozens of descriptions of encounters with prostitutes deepen an analysis of Graham Greene’s career? Apart from the autoerotic impulse that seems to drive some biographers, there is no way the intellectual substance of a book is enhanced by cataloguing similar kinds of evidence. More tiny facts do not mean more truth, whatever a positivist might say. As I get ready to write a book, I accept that most of what I know is only backstory.

So I won’t send that email to my publisher. There will be only one volume. And I want to make sure that it actually tells a story. Greene repeatedly put his life in danger, playing Russian roulette, trekking through the jungles of Liberia and Malaya, dive-bombing in Vietnam, investigating leproseries in the Congo, visiting guerrilla camps in the Dominican Republic, getting shelled in the Sinai, and tangling with the Mafia in Nice. In terms of character, action, and setting, a biography of Greene ought to have many of the virtues of a good novel.

As part of the task of making the book readable, I feel that I have to declare war on dreariness. Even in a dark moment Greene could describe his own life as “Useless and sometimes miserable, but bizarre and on the whole not boring.” Sherry and other writers have portrayed Greene as a fairly grim character. This is a partial truth—he was a manic depressive—but it is rather like seeing Woody Allen as just an unhappy man. I would like to pepper the book with Greene’s jokes. The author of Our Man in Havana and Travels with my Aunt was much funnier than we give him credit for. His gallows humour was relentless, and it can be used to invigorate the book without trivializing it. With the Edith Sitwell biography, I promised my editor a joke per page. I was particularly pleased by a review headlined “Eat Your Heart Out Dame Edna,” especially when balanced against another reviewer’s observation that the book was “sobering… sadness is never far from these pages.” It is perfectly possible to render both the humour and the sorrow of a life, just as it possible to think seriously about a writer in his or her time without inflicting misery on those who might buy the book. I have a year or so to do this job. What can I say? Pray for me.

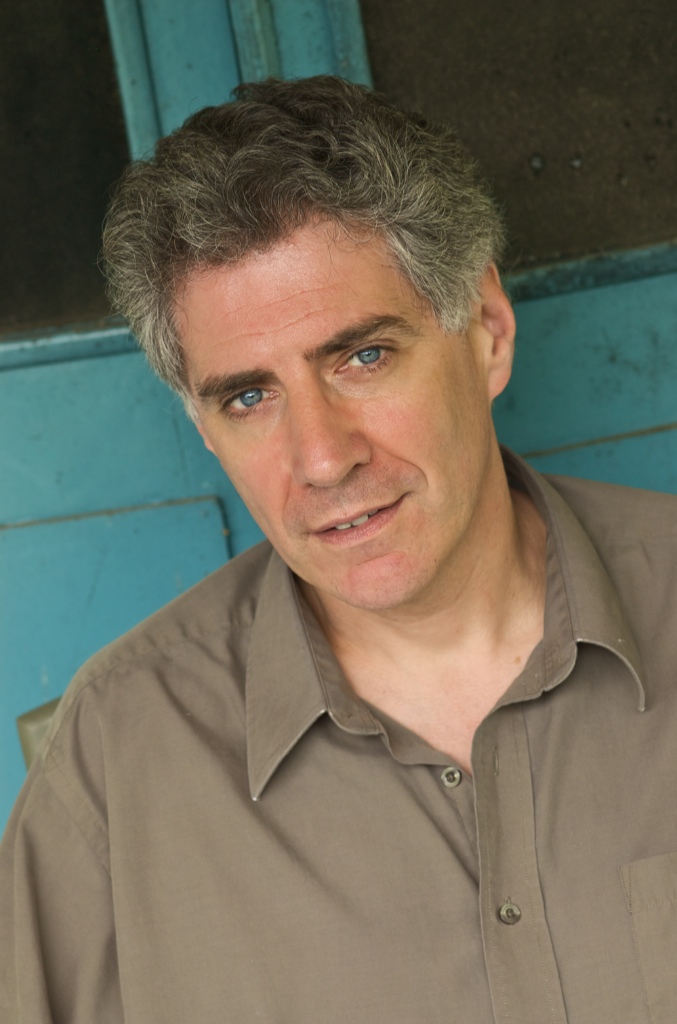

RICHARD GREENE's latest book of poems is Dante's House (2013). His book, Boxing the Compass (2009), won the Governor General's Literary Award for Poetry in 2010. He is also the author of several biographical works, among them Graham Greene: A Life in Letters (2007).

Photo: Linda Kooluris Dobbs