The Meeting That Saved Modernism

Robert Archambeau on how streetcar consolidation changed literature

HENRY DAVID THOREAU'S quip about the mass of men leading lives of quiet desperation never seems quite so true as it does when we find ourselves gathered around tables in conference rooms, documents spread before us, a voice doling out turgid paragraphs laden with numbers and acronyms. When sentenced to such a situation by financial or administrative necessity, we might take comfort in the law of unintended consequences, and imagine that what transpires around the conference table may, through some unlikely convolution of history, lead to truly momentous events, perhaps even to a flowering of artistic genius. After all, it has happened at least once before, in San Francisco, in the oak paneled meeting room of a railroad company office.

In 1893, a brooding young man of 28 strode into that office with a briefcase full of documents and nothing approaching artistic experiment on his mind. When he stepped out he carried even more documents, among them a sheet paper bearing the signature of Collis Potter Huntington, one of the greatest railway magnates and robber barons of the age—and this sheet of paper was to prove more influential to the modernist visual and literary artists than a dozen manifestos cooked up in the cafes of the Left Bank. The young man, Michael Stein, had just secured his future and that of the four younger siblings, Simon, Leo, Bertha, and, youngest of all, his bookish sister Gertrude.

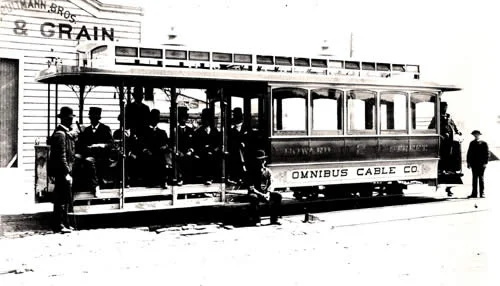

Omnibus Railroad and Cable Company streetcar

The Steins had been children of rootless privilege, living in a variety of hotels and luxurious rented accommodations before settling in a ten-acre spread in still-undeveloped Oakland, but when their parents died and Michael went through the documents of his finances, he found that his father’s chief asset had been a certain kind of imaginative moxie. Before his death in 1891, just shy of 60 years old, Daniel Stein had owned land in Shasta County and shares in the Omnibus Railroad and Cable Company, one of the eight rail lines then crisscrossing San Francisco. But the tables of profit and loss in his books didn’t add up—as Gertrude later put it in Everybody’s Autobiography, “There were so many debts it was frightening, and then I found out that profit and loss was always loss.” Michael took the reins, sold the Oakland property, and moved his brothers and sisters to a modest house on San Francisco’s Turk Street. Despite his dislike of all aspects of a career in business, Michael tried for two years to support the family by working for Omnibus Railroad, but soon found himself having to take more drastic steps. He had grown up listening to his father’s many far-fetched plans, but one of them—a scheme to consolidate San Francisco’s railroads into a single system—had stayed with him, and it was this plan that he took with him when he met with Collis Huntington to discuss selling the Stein shares in the Omnibus company.

Huntington was no pushover—born on a small farm out east, he had worked the land, trekked cross-country as a peddler, and followed the gold rush to California where he became involved in railroads that eventually spanned the continent. He understood all about industrial consolidation, eventually owning not only railroads but the companies providing train engines with coal, the companies manufacturing freight cars, and the shipyards that built the great vessels connecting his railroads to the world. Buying the Stein assets was a matter of pocket change for a man like him, but such was his industrial and financial muscle that, had he chosen to, he quite likely could have driven all competition from San Francisco effortlessly, leaving the Steins with a legacy worth of railway shares worth no more than the paper upon which they were printed. What he did find interesting, though, was a young man with plans, and he bought the Stein shares at fair value, not so much to acquire interest in another railroad as to acquire Michael himself. Soon Huntington had accomplished the integration of the San Francisco railroads, and installed Michael Stein as a regional manager. Michael disliked the work, but bided his time, and invested his capital wisely in local real estate. When he sided with strikers against Huntington and was dismissed a few years later, he was able to establish a trust that supported him and his siblings in reasonable comfort for life.

Stein's apartment, 27 rue de Fleurs

Michael’s meeting mattered, and not only for Gertrude—although, in the alternate timeline in which Huntington did not take a shine to Michael, it seems quite likely that Gertrude would have had to finish her medical studies at Johns Hopkins and, instead of writing The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, would have passed her time lancing boils in Baltimore. The meeting mattered because without it Paris would never have seen Gertrude’s longstanding salon in the atelier at 27 rue de Flerus. She and her brother Leo would never have put together the extraordinary collection of Picassos, Matisses, and Cézannes that drew hundreds of artists, novelists, poets, musicians, choreographers, and singers together. We’ll never know how much the artistic cross-fertilization that took place in that room mattered, but we can be sure it mattered immensely. To take just one incident: without the money Michael secured from Huntington, Gertrude Stein would never have met Picasso and, inspired by him, tried to do in language what he was doing in paint. We’d have had no Tender Buttons, and none of Stein’s “portraits” in writing—and without the effort that went into the making those we’d have nothing like the characteristic Steinian sentence. Writers as diverse as e.e. cummings, Sherwood Anderson, and Ernest Hemingway could never have written quite the way they did. Go back and read a page of Hemingway, substituting a “because,” “if,” “then,” “although” or “in order to” for every “and” and you’ll get a sense of how her flattened, paratactic style made his greatest moments possible, and rescued him from being a better-than-average contributor to Collier’s or The Saturday Evening Post.

When he died, Collis Huntington left millions of dollars worth of collected art to New York’s Metropolitan Museum. But his greatest contribution to the arts didn’t come from plundering Europe for old treasures. It came in a meeting that was unlikely to have been the most important one he took that week, or even that day, a meeting where a young man opened a case full of documents and nervously made his way through a presentation about the potential advantages of streetcar consolidation.

ROBERT ARCHAMBEAU's books include the studies Laureates and Heretics: Six Careers in American Poetry and The Poet Resigns: Poetry in a Difficult World, as well as the poetry collections Home and Variations, Slight Return and most recently The Kafka Sutra. He teaches at Lake Forest College.

LINDA BESNER talks to NYLA MATUK about her new book